Writer: Andrew Jones

Producer: Andrew Jones

Cast: Rachel Howells, Alison Lenihan, Lee Bane

Country: UK

Year of release: 2015

Reviewed from: online screener

Website: www.facebook.com/NorthBankEntertainment

It’s been a few years since I watched an Andrew Jones movie. Back in 2007 I reviewed his second feature The Feral Generation, a bleak drama about homelessness. At the time he was attached to a mooted remake of Driller Killer, and he wrote an unproduced remake of Beyond the Door for Ovidio Assonitis. He then teamed up with James Plumb to make three new entries in public domain franchises: Night of the Living Dead: Resurrection and Silent Night, Bloody Night: The Homecoming (both directed by James) and The Amityville Asylum (directed by Andrew).

In the past two years, Jones’ production company North Bank Entertainment has become a veritable film factory, pumping out a new low-budget horror every few months. And because Andrew is a reliable source of material, he’s having no problem finding distribution. In 2013 he shot The Midnight Horror Show (aka Theatre of Fear) in October and Valley of the Witch in November. In 2014 he shot The Last House on Cemetery Lane in April, Poltergeist Activity in September and A Haunting at the Rectory in November. All five of these are now available on DVD. Already this year, Andrew has shot Robert the Doll in February (out on DVD next month as just Robert), thriller Kill Kane in April and The Exorcism of Anna Ecklund in June!

Conjuring the Dead is actually a retitling of Valley of the Witch for its VOD release through the ever-reliable TheHorrorShow.tv. Announced for an October 2014 DVD release through 4Digital Media under its original title, that disc was evidently pulled, retitled and rescheduled for early August, making this July VOD release the film’s UK debut. (Hanover House released it in the States in January.)

Conjuring the Dead is actually a retitling of Valley of the Witch for its VOD release through the ever-reliable TheHorrorShow.tv. Announced for an October 2014 DVD release through 4Digital Media under its original title, that disc was evidently pulled, retitled and rescheduled for early August, making this July VOD release the film’s UK debut. (Hanover House released it in the States in January.)Anyway…

Rachel Howells (who was in Jones’ first film, Teenage Wasteland) stars as recently divorced Londoner Kristen Matthews who takes the opportunity of inheriting a house from her aunt to leave the city and move to the small Welsh town of Cwmgwrach. This is a real place, whose name translates as 'Valley of the Witch' and which has assorted legends attached, although I can’t find any record online of the historical part of this film’s plot. Incidentally, Aussie Prime Minister Julia Gillard was born in Cwmgwrach – although her PR people generally claim she’s from Barry!

Kristen befriends her neighbour Barbara (Alison Lenihan, variously a radio presenter, a cabaret artiste and a Cher tribute act) although she’s slightly freaked out to discover that Barb is a practising Wiccan who belongs to a small coven of white witches. Although Rachel is nominally the film’s central character, the picture’s heart lies in a magnificently subtle performance by North Bank regular Lee Bane (who has been in all of the company’s films since NOTLD: Resurrection) as Jim Eckhart, the local plod. Three suicides in swift succession, apparently unconnected and all allegedly happy individuals, suggests something strange is going on.

Among a succession of flashbacks, dream sequences and other interstitial elements which help to pad the slender story out to feature length – some of them featuring colour distortion effects of an intensity rarely seen outside of 1970s Top of the Pops – we learn of how three witches were crucified and burned in 1614. The leader of the three cursed the village in the traditional manner of horror movie witches – and evidently this relates to what is happening now.

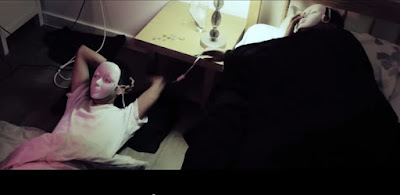

Kristen is attacked in her own home by a maniac in a hood and manages to stab him – but when PC Jim arrives, the body has disappeared and there’s not even any sign of a struggle. Truth be told, the ‘spooky’ things which happen throughout the film are somewhat random and don’t fit together in any way, leaving assorted flapping plot strands, not least the suicides which don’t seem to relate to anything else.

It is all, as one might expect, connected to the 17th century witch burning and certain people being direct descendants of certain other people. A family tree website is used to identify people’s ancestors although that doesn’t stand up to close scrutiny. All we see on each occasion is a name and a late 16th century birthdate, but only one of those names has any obvious meaning. More to the point, even at a conservative estimate of, say 33 years per generation, at a remove of four centuries each of us has about 4,000 direct ancestors. It’s unlikely they’d all be listed on a family tree website, but nevertheless characters do seem to somehow go straight to a specific name and we are left to infer that this particular ancestor was involved in some way in the witch burning.

Nor could it truthfully be said that the film’s final scene makes total sense; it’s unclear why this is happening and why the person doing it is doing it. On the plus side this scene, which is shot silent and in slow motion so that we see – but don’t hear – people shouting and screaming, is extraordinarily effective. Solid evidence, if any were needed, of how confident Andrew Jones is in his craft and his niche.

Jones does a good job overall in capturing the spirit of the small town, with its local copper, local priest and local shop for local people. Furthermore the film is remarkably well cast. Jared Morgan plays the priest. (God almighty – it’s the guy who was ‘interviewed’ by Uri Geller in the footage Jo Roberts and Jim Eaves shot when they turned Diagnosis into Sanitarium! Also in Footsteps and an obscure 2004 semi-documentary version of Journey to the Centre of the Earth.) Rachael Jones, Patricia Ford and Jessica Ann Bonner (Devil’s Tower, Serial Kaller, Christmas Slay) are the three witches, and the legend that is Kenton Hall (A Dozen Summers, KillerSaurus) clearly has a ball in his brief appearance as the Witchfinder General.

DP Ryan Owen Eddleston also shot Theatre of Fear and The Last House on Cemetery Lane for Jones and is currently prepping his own documentary entitled I am Dracula. Make-up effects are by Harriet Rogers who also worked on Amityville Asylum and SJ Evans' Dead of the Nite. In fact most of the crew have multiple North Bank Entertainment credits and/or have worked on other features and shorts produced as part of the 21st century Welsh horror boom.

Under either title, Valley/Conjuring is a solidly crafted, very watchable slice of serious low-budget horror that hits its targets. Many film-makers have talked in the past of establishing their own film factory to produce a catalogue of horror films, often citing some mythical version of Hammer as their model. In today’s marketplace, it looks like that’s a real possibility and Andrew Jones’ North Bank Entertainment has achieved something like that. I really should watch some more of his pictures…

MJS rating: B+